Rediff Business presents the TCS Smart Business Case Study Contest for managers, along with The Smart Manager, the management magazine! We give you a profile and the history of a company. All you have to do is study it and post your solution here, in 500 words or less. The best solution will win a cash prize of Rs 25,000 and a one-year complimentary subscription to India's first world class management magazine! The Smart Manager will also publish the winning solution along with your photograph.

Hurry! The last date to post your solution is July 10, 2007.

Hunger pangs: The case of internationalization

It is 9:30 a.m. on May 21, 2006. R Krishnan, president of South Indian Foods (SIF), is deep in thought in his office at the first floor of SIF House, the corporate office of the company in Coimbatore. He has just returned from a week long business trip to the United States, and is now probing the future prospects of his company.

His eyes gleam at the thought.

Obviously he is thinking about the company going international. At 10:00 a.m., he invites Shankar, the senior vice president (marketing) of SIF, to his office.

"Having put forth an excellent performance in India over the past sixteen years, why can't we think of going international?" asks Krishnan over a cup of steaming coffee.

"Our channel strategy did click very well in the Indian market. With state-of-the art production facilities and our marketing expertise, I believe we could easily create a niche overseas," he continues.

"Yes, it's high time we took a step in this direction. I too favour this idea," chips in Maya Krishnan, Krishnan's wife and vice president (operations) at SIF. "But how should we go international? I mean, in terms of production and distribution."

Shankar intervenes, "We have a very good presence here in the Indian market. Also, our experience in handling products would be a great asset if we decide to go abroad. I believe, it is the right time to tap the foreign markets to maximise our sales. But before that we need to conduct a viability study and country analysis."

"I think, even before that, we need to have a list of the probable markets abroad," said Maya.

Krishnan closed the discussion with a call for an emergency senior management meeting on 22 May at 10:00 am to discuss the matter in detail.

Company background

SIF emerged as a private limited company in the Indian market with a strong product line during December 1989. Until then, no company had thought that such a product line would be accepted by so many customers. Its three innovative products, Easy Idly Mix, Easy Dosa Mix and Easy Appam Mix, were in fact winning the hearts of South Indians.

As a director of South India Beverages Pvt Ltd (SIB), Krishan had seen tough times in the late 1970s. It was a period of deep recession and unstable governmental regulations.

Many industries suffered setbacks during this period, and SIB was no exception. Unable to withstand market forces, as inventory began to pile up, Krishnan began to look around for something new and different to do.

Now in his late 40s, Krishnan was a postgraduate from the Indian Institute of Management. He displayed an entrepreneurial bent from childhood. His first job was in a direct marketing company where he spent over five years. Later he floated his own company, SIB, with the help of his father, B K Nair.

In 1981 he married Maya, a postgraduate in food and nutrition with a keen interest in cooking. As a hobby, Maya used to help her neighbors learn to cook different variety of dishes.

Sometimes she and her neighbours would prepare mixes which could be eaten as a side dish or with rice, the staple of the South Indian diet. Homely and good at taste, many of her friends started buying these items from her.

Krishnan encouraged Maya. In December 1981 he even appointed two women as helpers so that she could make these products in larger quantities such as mixes of 5 kg to 10kg as well as packages of 50 gm and 100 gm. Gradually nearby groceries began to stock her food products in small packets and bottles, as unbranded commodities.

Her husband, however, was not doing as well. By 1988, the beverage industry had totally flattened. Only a few big players hung on, the rest had to give up. SIB was dissolved. Krishnan began to help his wife in preparing and selling the food products, and SIF began to take off in a big way.

1989 saw the introduction of an innovative batter from which idlies, dosas and appams could be made easily, an innovation which multiplied SIF's sales and potential. More manpower, newer and improved machineries, large production capacities, and better quality control techniques became necessary, which in turn resulted in economies of scale.

It encouraged the husband and wife team to register SIF as a private limited company. In May 1995, SIF decided to go public. As expected, investors responded positively.

Production

Though the company started with only three products, it offered twelve products by 1997. Aside from the initial batter innovation for idly, dosa and appam, SIF now made pastes (tomato, tamarind, masala), flour (rice, wheat, groundnut), papads (rice, masala, gram), and fryms (vadams). SIF rapidly emerged as one of the major players in the market.

In October 1989, SIF moved out of the Krishnan kitchen into its own production unit. Until then the raw material for Maya's batters and pastes were purchased in small quantities from local markets and the processing was done manually.

Since the production was on a small scale, Krishnan and Maya used to supervise the entire production process themselves. The batter was stuffed into polythene bags of 250 gm and 500 gm with the help of a few hired laborers.

Post 1989 production was carried out in a large shed; and uniforms were provided to workers to maintain cleanliness. Maya personally supervised the production process. Despite the larger volume of production and the attraction of longer shelf life, SIF maintained its policy of no added preservatives. Demand grew for all its products.

SIF had a separate wing for quality control and analysis, equipped with a modern laboratory, which ensured quality at three stages of production. Stage one analyzed raw materials, stage two tested finished products before packing, and stage three examined the packing to ensure that it was bio-compatible and leak-proof. The laboratory was sophisticated and well equipped. Its quality control staff was sourced from Kolkata's Indian Statistical Institute.

Early days

SIF's market was essentially centered in and around Coimbatore, and covered the neighboring towns of Pollachi, Tiruppur and Palakkad. Local vans dropped off finished products to wholesalers and retailers.

Within four years of production, by 1993, the company had two more production units located at Bangalore and Chennai to cater to the whole of South India.

The products were packed in 'environment friendly' plastic bags, sachets and plastic disposable containers. By then SIF had started adding 'class preservatives' to the batter for limiting fermentation and to keep it fresh for at least ten days. Vinegar was used as a preservative in the case of pastes.

By 1994 each of SIF's three units had a monthly production of about 15,000kgs of batter and 2,500kgs of paste. The high market demand encouraged Krishnan to take their products to the whole of India. This led to the launching of three more manufacturing units, one each in the states of Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal.

Fast forward

In order to achieve better penetration, SIF had to extend its product line, and thus it started manufacturing papads and fryms. However, just when the Krishnans increased their production capacity, competitors crowded into the market.

To address the issue of competition, SIF ventured onto its competitors' turf by making dry-flour and sooji.

SIF started making dry flour in its existing in Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh, its two biggest units. The location of these units was based on the availability of rice from Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, and wheat from Northern India. Moreover its competitors also had their operational bases at these two locations.

In keeping with its traditions, SIF used the best quality raw materials (particularly grains which were the major ingredient of its products) from the best available sources.

While rice was sourced from South India (mostly from Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh); wheat was sourced from Punjab, Haryana and Maharashtra; grams from Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra and West Bengal; pulses from Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh; and preservatives, vegetables, spices and oil in bulk from the local markets.

SIF used imported machinery for pressing, grinding, cleaning and packing. Qualified and professional staff were employed to supervise and check for quality during the production process. The plant utilisation capacity, which had hovered around 40% in the early 1990s, grew rapidly to 90% by 1998.

Gradually production capacity was enhanced so that by 2006 its three plants were producing 360 tons of batter, 60 tons of paste, 15 tons of dry flour, 10 tons of papads and 5 tons of fryms.

Quality was important at SIF. The word 'quality' at SIF meant traditional purity combined with the latest technology to give a perfect blend of South Indian taste to the consumers. SIF employees were proud of their association with the company. Indeed they had many reasons to be so.

Not only were the compensation packages the best in the industry, but also there was a sense of oneness in the SIF empire. Though the atmosphere within the company was formal, the 650 employees cherished the friendly atmosphere.

Packaging

SIF took great care in designing the packaging as most of the products the company handled were perishable. The aroma and freshness of the products also had to be addressed carefully, as also the issue of shelf-life. Batter, prone to fermentation, was found to be best packed in the combination polyester and LLDPE.

The pastes were normally bottled in glass jars. SIF had a unique way packing papads and fryms in 'foil liner pack' which help locks in the crispness and freshness for at least two months.

Packaging was completely automated. While batter products were packed in quantities of 250gms, 500gms and 1kg, pastes were packed in attractive bottles of 250 gm and 500 gm. Papads were available in packs of 250 gm and 500gms; and fryms in 250 gm and 500 gm packs.

Competition

In the South India papad market, SIF enjoyed a 23% market share. Its closest competitor was Durga Papads, which had a wide range of papads and a 14% market share. Durga Papads was planning to expand to Northern India.

In the dry flour market, SIF held a 22% market share, and its two biggest competitors were Bhavana Flour Mills and Shanghi Flours with a market share of 12% and 18%, respectively.

In the batter market SIF was the major player with a 27% market share in the organised sector. However there was stiff competition from new entrants like Akshaya Foods and Swathy Foods which had grown to 12% and 17%, respectively, in the organised market in India. A well run company, Swathy Foods competed with SIF also in papads and dry flour, having garnered market share of 7% (in papads) and 5% (in dry flour).

Marketing

Initially production was on a small scale, and distribution done with the help of delivery agents. Increasing demand led to large scale production, necessitating promotion. The early advertising campaigns were executed through local newspapers and radio. In addition, handbills, printed in the local language, were distributed along with morning newspapers in select towns.

Specific advertisements showcased traditional flavor, and taste was linked with the culture and heritage of India. Typical, quality, South Indian food items with great taste was the message. As a result, awareness about the product increased and thereby the demand.

SIF also offered sample packets of batter products to customers who purchased other products of the company. The promotions and special offers were popular and helped SIF become a household name in the Indian market.

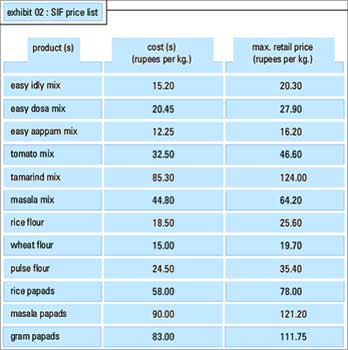

In keeping with general practice, wholesalers got a margin of 2% and retailers 8% on SIF products. Retailers who made sales more than Rs 5,000 got an additional 1% margin. Exhibit 02 shows the product wise costs of production and the corresponding list price.

Distribution

Until 1992 the distribution to retail outlets was through a direct sales force, and some orders were also taken at the production center. Once the factory was up and running, making a larger number of products, Shankar saw the need for a broader distribution channel.

Two options were thought of. The first was to setup a distribution unit within the organisation, and the second was to hire exclusive dealers.

In April 1993 the company took the second option because of its low overhead costs. Twenty dealers were appointed across the country. Before entering into a contract, each dealer's credibility and capacity to undertake and supply a large volume of goods were scrutinized carefully by Dinakar, vice president finance.

Under the terms of the contractual agreement, 'sale' to a dealer meant the transfer of possession of goods to the dealer for a wholesale price, who in turn would arrange the supply of goods to retail outlets.

Dead stock after their expiry period was taken back by the company. This came to an average figure of 2% on total sales. This arrangement worked very well until the mid 1990s given the size of the company.

By the mid 1990s however, SIF's growth required a new structure. A three level (stockist-wholesaler-retailer) distribution channel system was developed with a new discount scheme. The new advertising and marketing campaigns supported the new network.

However, though the company had successfully achieved a wide reach in urban India, it was not able to penetrate rural markets, as the people there were not ready to accept the 'readymade' version of their traditional food-items. This was considered a great failure as more than 70% of India's population live in villages.

Global plans

As decided, the Executive Board met at 10am on 22 May 2006. Those present were Krishnan (SIF's president), Maya Krishnan (vice president-operations), Shankar (senior vice president-marketing), Sunder (vice president-marketing research & sales), and Dinakar (vice president-finance).

Krishnan: "Well gentlemen, I shared with you what came to my mind. I would appreciate if you could tell us your views".

Sunder: "We have to be optimistic about the US market. As you know the Indian population there is large enough to absorb our products. Our market research also revealed that Indian dishes are favored by even local Americans".

Shankar: "I accept your views Sunder! But we are forgetting the fact that in the US market, we have to compete with powerful 'tinned foods'. Considering our limitations, I believe we should start exporting to the US at the earliest. Once we are able to catch up with the US market, we can think of investing in the US."

Krishnan : "Do you think the Asian market is barren? Considering the fact that the raw material is readily available, at least South Asia could provide us good sales."

Maya: "I do not think targeting entire Asia is a viable option. Though the Chinese and Japanese are accustomed to rice, culturally most of these Asian countries are different from India. Also why not European countries like the UK, where there is a considerable number of South Indian population? "

Shankar: "That makes our job much more complicated. The reason being, convincing them to go for our products. . ."

Dinakar: "Why not productions centre in the United Kingdom or the United States? I believe production overseas would be a better choice, as the overheads then could be brought to the minimum".

Shankar: "Instead of setting up a production unit overseas, why not licensing options to the US and the UK?"

Krishnan: "Well, I think, we need to analyze the various possible options. Perhaps a detailed cost-benefit analysis would be of great help to us. . . Thank you very much gentlemen. We may have to meet here again next week for a decision making exercise. Thank you all! "

After the meeting of the Executive Board, Krishnan and Shankar discussed the situation and listed four strategic options for the internationalization of SIF:

- Enter into licensing agreements with mid-size food companies in the US and the UK for carrying out production and marketing operations in those countries.

- Produce more in India and directly export to other South Asian countries, the US and the UK.

- Produce more in India and export to other South Asian countries, the US and the UK using the services of distribution agencies based on these countries.

- Set up a production centre in North America to cater to the needs of the customers in Europe and the US.

Your question

Should SIF go global? If yes, what should be its strategy? If no, why not?

Published with the kind permission of The Smart Manager, India's first world class management magazine, available bi-monthly.