He said the prime minister represented the nation and even if we disagreed with his policies or programmes, the right forum for expressing it was swadesh, that it was utterly improper for any Indian to do this on foreign soil.

After the 1962 war with China, emotions ran high and Nehru's policies came under attack. An article in Panchjanya criticising Nehru was a bit harsh on his personal style, and again Pandit Deen Dayal Upadhyaya (one of the founding leaders of the Jana Sangh, precursor to the Bharatiya Janata Party) disagreed with the tone and tenor of the piece, though the Jana Sangh had vehemently attacked Nehru's policies.

In a democracy freedom of speech is sacred and the right to criticise is a significant fundamental one. But should it also be allowed to go awry and distasteful? Democracy thrives on the strength of institutions and individual freedom depends on how we support and respect these institutions.

Of late we have been witnessing continuous erosion in the authority of such institutions that are the basic pillars of the State. One reason for this may be that inept people adorn the high pedestals of such institutions. Yet it is our dharma to see that corrections are made even at the cost of swallowing some biter pills.

During the unsavoury beef tallow scandal, a Shankaracharya supported the culprits for political reasons. Still, all the RSS publications were instructed not to use any derogatory word against him, as it is our duty to protect the sanctity of the ochre robe.

Men may err, but institutions should survive. That was the reason Indira Gandhi was highly praised by Atal Bihari Vajpayee -- who was otherwise a bitter critic of her policies -- after the 1971 victory over Pakistan.

Even during the P V Narasimha Rao regime, Vajpayee advised against personal attacks on Sonia Gandhi or Rao. Being harsh about the ruling party's policies is what democracy demands, but getting personal is unfair in a civil democracy.

The powerful democracies like the US and UK have consolidated their foundations not on the strength of the written word but on the observance of the unwritten code of conduct. Their past presidents and prime ministers have not been subjected to personal questioning or sent to gallows by their successors.

The situation is altogether different in Islamic regimes like Pakistan and Bangladesh, where a change in regime means changing all photographs of previous rulers adorning office walls and schools. No incumbent ruler ever says a nice word about his or her predecessor and everyone else becomes an object of hate and ridicule.

India can proudly claim that whatever the colour of the regime, none have instructed the removal of the photographs of national leaders whom the new dispensation had opposed.

I have seen the busts of Pandit Nehru and Rajiv Gandhi in the room of Ananth Kumar, then (the BJP) civil aviation minister, and when I simply smiled, he guessed my question and said -- after all they were India's leaders.

L K Advani had a large portrait of Sardar Patel in his office chamber, though Sardar was a Congress leader. The day he was sworn in, the sad news of EMS' (E M S Namboodripad, a Marxist who was the world's first democratically elected Communist chief minister) demise came and Advani was there at his cremation in Thiruvananthapuram offering condolences.

That is how people of the Hindutva hue behave. But the first instance of intolerance in recent times was exhibited when the UPA government ordered the removal of all portraits of Deen Dayal Upadhyaya from its offices, and even those of Swami Vivekananda were taken out from the Nehru Yuva Kendra head office.

The intolerance towards an ideological opponent is an un-Indian trait brought here by jihadi invaders and in modern times by the Leftists. These are times when vendetta about ideological differences have become a matter of routine.

So a State which is just 59 years old found it easy to assault a spiritual constitutional seat representing five thousand years of civilisational flow -- in Kanchi.

Manmohan Singh too has shown that he trusts a general, responsible for Kargil and the resultant martyrdom of our young jawans more than he trusts his Indian fellowmen in the Opposition. Never has he thought of taking the principal Opposition parties in confidence, who have also ruled at the Centre, before taking any crucial decisions that have a bearing on the nation's future.

An ideological opponent cannot be an enemy and patriotism cannot be the property of the chosen few. Every political party and organisation works towards the betterment of society and the nation in its own way, makes compromises and mistakes which the present political system necessitates. Unless we see the compulsions of the system where to get elected by hook or crook matters most, we can't get rid of ourselves from deadly enmities against a view point we disapprove of.

The only port of hate and unapologetic enmity should be reserved for anti-nationals. Unfortunately, India is passing through an ugly phase of political hate and revenge killings just on the basis of ideological apartheid. If one kind of apartheid is bad, how can you justify the other kind?

The language and style of many a political bigwig has crossed all limits of decency and ironically the media laps it up for adding some masala or to please the corridors of power.

When I met Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and wrote a positive piece on him, the so-called secular (read intolerant) media created a furore on two counts -- first, why did the PM meet a saffron journalist and second, why I wrote an uncritical piece on him.

A Marxist can be accommodated in any of the mainline journals or channels but to be saffron has been made into a 'sin' in this land by the flag bearers of 'tolerance and peace'.

I wrote that piece because I thought Manmohan Singh had been trying to act in a difficult position in his own way and though we now criticise his many policies including the recent Havana adventure and 'peace talks reaching nowhere' unsparingly, it would be silly of us to doubt our prime minister's patriotism or intentions.

At best we can say he is getting trapped because of the Indians' basic nature of trusting everyone and following a mirage of peace with untrustworthy generals. The harshest criticism is simplest in words and exercising restraint in expressions is the first requirement of a strong democracy. As Vajpayee said, we can't write a poem for a great India with acid and hatred filled pens.

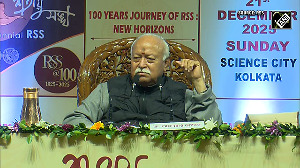

Tarun Vijay is the editor of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh weekly, Panchjanya, He can be reached at tarunvijay@vsnl.com