There are many reasons why Las Vegas is called Sin City. But gymnastics has never been one of them.

On a recent Saturday night, a mile from the casinos, lounge acts and lap dances that unfold along the Strip, several thousand children and their parents stream out of their minivans and SUVs, into the University of Nevada's Thomas & Mack arena, to catch a glimpse of their favorite Olympic gymnast.

The arena goes dark, except for a patch of light in the center of the floor, and a heavy beat comes on, letting you know, in case you were wondering, that this isn't going to be your typical gymnastics event. One by one, each of the shadowed figures standing outside the lit area enters it, and the evening's master of ceremonies, former gymnast John Macready, announces their names.

Courtney Kupets. Annia Hatch. Terin Humphrey. And on the men's side, Jason Gatson, Raj Bhavsar, Brett McClure.

When Mohini Bhardwaj's name is announced, and the tiny gymnast struts onto the floor, the applause gets louder, with parts of the crowd up in the stands roaring their approval. Only Carly Patterson, the last name announced, draws a better response, and that's understandable -- at 18, a couple months after winning the all-around Gold Medal at Athens, Patterson may be the most popular gymnast in America; the natural, if less celebrated, successor to Mary Lou Retton, who won gold in 1984. Like teammate Paul Hamm, who won the men's gold medal, Patterson immediately ascended to the pantheon.

But something unusual happened this year at the Olympics. The US women's team, billed as one of the best in history, came up against a tough format and, a Romanian team that suddenly seemed incapable of making mistakes.

Some of the young American women stumbled at crucial points, and the team found itself out of the lockstep rhythm that had made it appear invincible coming into Athens. Into this opening stepped team captain Mohini Bhardwaj, 25, who along with Cuban-born Hatch was the oldest American woman in 40 years to compete in Olympic gymnastics.

Bhardwaj was solid, narrowly missing out on individual medal contention but coming through in the clutch to deliver several strong performances and ensure that the team won a silver medal. But it was on the sidelines that Bhardwaj secured her legend. When younger, more hyped teammates started despairing over missteps, Bhardwaj exercised seniority and helped restore morale.

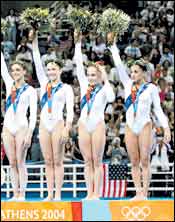

It was an unexpected turn of events, one that NBC's cameras and commentators zeroed in on -- calling her America's Sweetheart at times -- and by the time Patterson, Bharadwaj and teammates stood to acknowledge their team medal, their heads draped with olive wreaths, a new narrative had been written.

According to the revamped story, gymnastics was no longer the exclusive province of the young and the golden boys and particularly girls who perform agile, fantastical feats and who seem to be whole, unsullied. While practically every sport in America has its dark side -- blockbuster athletes who make outrageous incomes while performing spectacular transgressions on the side -- gymnastics has largely avoided the pattern.

The worst that could be -- and often was -- said of American gymnasts was they bore little resemblance to reality, that the sport's obsession with youth was unnatural and crowded out what was most grand about sport in general -- its ability to move audiences long after the show was over.

That is, until this year.

Several days after the Las Vegas show, the gymnasts are in San Antonio, at the SBC Arena. Their national tour, the TJ Maxx Tour of Champions, is billed as a combination of physical prowess and Cirque du Soleil style exhibitionism.

Several days after the Las Vegas show, the gymnasts are in San Antonio, at the SBC Arena. Their national tour, the TJ Maxx Tour of Champions, is billed as a combination of physical prowess and Cirque du Soleil style exhibitionism.

It's an annual event, but this being an Olympic year, it is a victory lap for the young men and women on the team who are basking in the post-Athens glow. Although the tour is tiring and time-consuming -- involving 40 cities and lots of road travel -- the gymnasts are generally laidback and tend to horse around in the warm-up sessions before each show, walking around on hands, doing successive back flips, swinging from uneven bars and displaying, without effort, the genius of their limbs.

Mohini has been asked to participate in a pre-game panel. About 100 children and their parents are set to filter into a section of the stands, where they can ask questions of their favorite gymnasts.

At the last minute, though, she decides against it so she can be interviewed for this article. It has been nearly impossible to track her down; her busy touring schedule -- 32 cities in a little over a month -- means she's often traveling between cities or practicing for her next show. But from conversations with associates, it's fairly clear Mohini doesn't enjoy receiving media attention. It was only after she returned from Athens that it became clear to her how popular she was.

"I had no idea they showed me in so much detail," she said of NBC and its Olympic coverage. "You're in a bubble. You come back and you get all this attention. It's kind of awkward, being recognized in the store or walking down the street. I like the fact that I had little time to be recognized and could go back to being a normal person."

We had moved out of the main arena, into a quiet, windowless back room, one normally used by the San Antonio Spurs for post-game press conferences. Mohini has long hair and broad shoulders. Her features are of the kind that has fans waxing poetic online and her coaches and handlers dreaming up endorsements for lucrative brands.

Although she's only 4 feet 10, she comes off as taller -- in part because she moves and speaks with such self-assurance.

There are a few tattoos on her body -- most recently one on her left wrist, of the Olympic rings.

"I got it done in St Louis," she said, "We had a day off. Me and one of the guys went and did it. Pretty much everyone who has gone to the Olympics has one."

But it's not her appearance or recent success which have been most influential, which have caused others, even people older than her, to change careers or to return to school at an advanced age.

For true gymnastics fans -- and there are many -- Mohini is a survivor. She displayed phenomenal talent at an early age, competing with girls older than her, before trying, and repeatedly failing, to go all the way. Her story is well known, as are the forces that long conspired against her success.

"For a lot of the older fans, Mohini has been a fan favorite," said Chris Korotky, editor of Inside Gymnastics magazine. "She was a rising star. At the 1995 National Championships, she placed in the Top 15 in the all-arounds. That's always the watch group for possible contenders for the Olympics the next year. She was very much on the radar screen."

She didn't stay on that screen, though.

Part II: Living life on her own terms

Pictures: India Abroad Person of the Year 2004

Read about:

India Abroad Person of the Year 2003

A community honours one of its own

Photographs: Getty Images

Image: Rahil Shaikh

More from rediff