The Rediff Special/Jeet Thayil

,

,

WHEN Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul won this year's Nobel Prize for Literature, Joe Cuomo, who organises the Queens College evening readings in New York, found himself both delighted and dismayed.

He was happy that Naipaul had received a long-overdue honour. But he also wondered if the author would fulfil a commitment to read at Queens College.

He needn't have worried.

At a time when New Yorkers are staying away from the city, frightened off by anthrax and other worries, Naipaul boldly arrived and did his bit. In fact, at his first public reading since the Nobel announcement, the laureate appeared to be his usual curmudgeonly self, except for one thing. He seemed laidback, a kinder, gentler version of himself, despite his well-documented ferocity that came growling through every so often.

He stood at a pulpit that had 'Queens College' written in black on brass, before a pipe organ in the campus concert hall. The reading from Half a Life was delivered with practised ease, every inflexion burnished, each character given a voice, each voice ringing out.

Naipaul picked a comic section about a dinner party given by a friend of Willy Chandran's. The audience laughed appreciatively at the funny parts and there were many.

At one point a man and woman, each deluded by the other, have this exchange:

"I thought you were a Marxist."

"I thought you were rich."

He read a passage about Marcus, who is "dedicated to inter-racial sex and quite insatiable." Marcus has two ambitions:

"The first is to have a grandchild who will be pure white in appearance. He is half way there. He has five mulatto children, by five white women, and he feels that all he has to do now is to keep an eye on the children and make sure they don't let him down. He wants when he is old to walk down King's Road with this white grandchild. People will stare and the child will say, loudly, 'What are they staring at, Grandfather?' His second ambition is to be the first black man to have an account at Coutts. That's the Queen's bank."

"The first is to have a grandchild who will be pure white in appearance. He is half way there. He has five mulatto children, by five white women, and he feels that all he has to do now is to keep an eye on the children and make sure they don't let him down. He wants when he is old to walk down King's Road with this white grandchild. People will stare and the child will say, loudly, 'What are they staring at, Grandfather?' His second ambition is to be the first black man to have an account at Coutts. That's the Queen's bank."

After the reading, Cuomo and Naipaul conversed about the novel. Cuomo spoke far more than Naipaul. He presented his views of the book, providing an instant review and plenty of analysis. There were audible complaints from the audience that the writer was not being given a chance to speak.

At one point Naipaul said, "If we go on like this, we'll give the subject away. I can't review my own books."

At another, he said, "I didn't think of it like that, I was just working with the material I had, you know?"

The crowd roared with laughter. Cuomo was the punch line, but he did not appear to notice.

After a particularly long literary dissertation by Cuomo, Naipaul said, "I feel like I'm on a psychiatrist's couch... Look, I just write the books!"

Finally, while talking about his non-fiction books, the writer spoke of his technique.

"I listen carefully. I do not insert my own voice," he said, fixing Cuomo with a baleful gaze.

Cuomo brought up Islam. "You are one of the most misunderstood writers," he said.

"Yes, but those people do not matter," Naipaul bristled. "The work has outlasted them. Let's not talk about it anymore."

Vigorous applause.

Naipaul then referred to "the fanaticism by which we are surrounded" and pointed out that people with no faith in anything else turn to religion with special fervour.

He said Islam as it was practised in some countries, particularly Indonesia, was a religion without "conscience". "The idea of private conscience is far from Islam," he said.

At the book-signing after the reading, Naipaul said he would sign only copies of Half a Life. He broke that self-imposed rule twice. The first time for an elderly west Indian lady who said, "It was such a pleasure, I met you 10 years ago", as she presented a copy of Half a Life and one of A Way in the World.

Naipaul thanked her and signed the new book readily enough. When it came to the older book, he hesitated, then signed it, muttering, "This delays the whole process."

A few signings later a young man with a copy of Beyond Belief presented it. "I may sign this quickly," Naipaul said. "But you should have bought the new book."

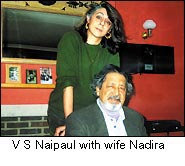

"Now don't get grouchy," his wife, Lady Nadira, gently admonished from a spot on his right.

"Now don't get grouchy," his wife, Lady Nadira, gently admonished from a spot on his right.

"I'm not getting grouchy," Naipaul replied. "But there is an etiquette about these things."

Soon enough John Simon arrived clutching two shopping bags full of books. A bookseller in Pennsylvania, he drove for two hours to make it to the reading with every copy of Naipaul's books that he could find. He did not bring a copy of Half a Life because it had not arrived at his store yet. Naipaul refused to sign Simon's books.

After the reading Simon stood outside the campus building as people filed out. "I have nothing against him winning the Nobel," he was heard to say. "But I can understand why Paul Theroux doesn't like him."

Simon was angry, he said, because he did not even get to speak to the writer. Nadira Naipaul had told him off and she had not been too polite about it either.

An Indian man asked if he could shake Naipaul's hand. Naipaul obliged. "I saw you in Guyana when I was 12 and you were researching The Middle Passage [Naipaul's first work of non-fiction]," the man said. "My mother remembers you very well."

"How nice to see you again," Naipaul said.

After the signings, Naipaul got up from the table. "How many copies did we sell?" he asked.

"There were a hundred copies," Cuomo said. "They were all sold."

"Sold out, every single one," said a woman who had been supervising the event. "They went like hotcakes."

"All sold!" Naipaul said. "Every one!"

"Are you surprised?" his wife asked.

She, clearly, was not.

ALSO READ:

'When Sir Vidia cried...'

'Naipaul is a blunt man'

Naipaul deserves Nobel: Merchant

Indians not intellectual enough 40 years ago: Naipaul

Naipaul, Rushdie among favourites to win Nobel

EXTERNAL LINK:

Know more about V S Naipaul

The Rediff Specials