Ketan Mehta's stopover in Locarno this August may be termed 'The Return.'

Ketan Mehta's stopover in Locarno this August may be termed 'The Return.'

The world premiere he attended of The Rising - Ballad of Mangal Pandey, also marks his first film in eight years.

The saga of one man's rebellion against a great colonial power opened the 58th Locarno International Film Festival on August 3. Mehta basked in the enthusiastic applause that greeted the screening.

Quiet, thoughtful Mehta has made a spectacular movie quite unlike himself. He believes cinema should hold up a mirror to the way the world is going. Even if the film is a historical? Yes. This is certainly a common thread underlying a lot of his films. He works the way he thinks.

The Rising: History comes alive

Ketan Mehta arrived on the Indian film scene in the 1970s and 1980s, when creative talent suddenly began to spring and surge all over the country. He was prolific and showed rich promise as early as in his second film, Bhavni Bhavai (1980). This was a sardonic allegory of India's terrible caste system. Mehta first made films in his own language, Gujarati. Only then did he branch out into Hindi filmdom. All his subsequent work, Holi (1984) and in particular Mirch Masala (1987), was rooted in an original, deeply committed cinematic mind.

Mehta is now in his early 50s. He studied economics before turning to something he had always hankered after: cinema. He graduated from the Film and Television Institute, Pune. His filmography comprises 10 features: The Rising -- Ballad of Mangal Pandey, 2005; Aar Ya Paar, 1997; Oh Darling Yeh Hai India, 1995; Sardar, 1994; Maya Memsaab, 1993; Hero Hiralal, 1988; Mirch Masala, 1987; Holi, 1984; Bhavni Bhavai 1980; and Toote Khilone, 1978.

In Locarno, he spoke to Uma da Cunha about the eagerly awaited The Rising, produced by Bobby Bedi and starring Aamir Khan, Rani Mukerji, Amisha Patel and the English actor Toby Stephens.

In your opinion, what is the role and impact of cinema on society?

Cinema is the most powerful medium of communication ever created. And in India, its fascination is total. It can influence our beliefs and thinking. I like to link my films -- even if they are period films -- to the world around us, in our time and experience.

Cinema is the most powerful medium of communication ever created. And in India, its fascination is total. It can influence our beliefs and thinking. I like to link my films -- even if they are period films -- to the world around us, in our time and experience.

The Rising, for instance, is a metaphor and allegory -- a mirror held up to the world we are living in today. It is centred on the spirit of freedom that connects nations in many ways. It has a meaning in today's traumatised world, threatened by the events in Iraq, Iran, the free market. A film can look presage a warning.

A hundred years from now, it could be that Enron, Microsoft, the market can rule the world. Seeing current events as precursors of possible threats and dangers to a way of life is something we should be concerned about. We are living in global villages today, with processes surfacing in an ominous way. We should be concerned and wary. This is what I have attempted as a link in The Rising.

Special: Showcasing Mangal Pandey

What is your advice to a newcomer entering films as a director?

He or she should be open to the world we live in and feel a concern for it. They must learn that cinema can play a big role in the way we live, and, handled well, can resonate and influence.

Why have you kept away from directing films for so many years?

It is not out of choice, believe me. But I have always been interested in advances in cinema technology. In the mid-1990s, I started a company called Maya Entertainment, a digital animation and special effects studio. That is an exacting and demanding task and left me no time for making films myself.

How did you get involved in the making of The Rising?

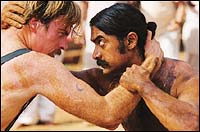

I wanted to make this film 17 years ago and was waiting for the moment when the idea would be realised. This film is a historical epic set in 1857. All of the Indian subcontinent was then ruled by Britain's East India Company. One small rebellion toppled this imperial edifice.

I wanted to make this film 17 years ago and was waiting for the moment when the idea would be realised. This film is a historical epic set in 1857. All of the Indian subcontinent was then ruled by Britain's East India Company. One small rebellion toppled this imperial edifice.

How did you assemble such an exceptional stellar cast?

We have been fortunate to get the best talent for a film that will be seen globally. Three years ago, I asked Aamir to star in it. He was at the peak of his career. Since then, he has focused all his time on this project.

Rani Mukerji loved the script, enough to accept what was a cameo role. She made it clear she wanted to be in the film. Her role grew as we worked on the script -- and now hers is an important part.

The others, Amisha Patel and Kirron Kher and many others expressed their keenness to be in the film. We are really fortunate to have Toby Stephens for the main English character -- the British officer with a conscience. Toby is the son of Dame Maggie Smith and the late Sir Robert Stephens -- a man born into theatre, who is a fine stage and screen actor.

Buy Mangal Pandey movie tickets!

Why does the British Officer William Gordon, have such a key role?

Captain William Gordon, played by Toby Stephens, is largely a fictionalised character, and he introduces another way of looking at the events of the time. He serves as a balance to the growing Indian patriotism of the period.

The film presents multiple points of view. Gordon is a footnote in the recorded history of that time. There is just a mention of a British officer helping the rebels. Sitting with writer Farrokh Dhondy, we wove in the friendship angle. Very little is known historically of Gordon, or even of Mangal Pandey. After researching that period thoroughly, I was left with just two pages on the legendary Gordon.

So, in the film, we have extrapolated fiction from facts and we have dramatised events. There has been a lot written by British people of that time, there are letters and so on. So, re-creating the spirit of that time was a challenge that was creatively stirring.

Has the content of The Rising been sanitised to appeal to an audience abroad?

Has the content of The Rising been sanitised to appeal to an audience abroad?

Not at all. In The Rising, we have tried to retain the Indian-ness of the subject in the way it is made, and then seen how best we can convey this to the world at large. There has been no conscious effort to design the film with an eye to the international market. To serve both, we have shot the film simultaneously in Hindi and English, because we wanted to avoid dubbing or subtitling.

In The Rising we have blended cinematic styles. There are the songs and dances that are so essential an element of the Hindi film, then the heightened cinematic narrative along with a running ballad that testifies to the hold that the legendary Mangal Pandey still has on an audience. Underlying the film is the oral tradition of Indian folklore.

Why the archive ending, with Gandhi leading the way?

We wanted to draw a parallel and connect the years 1857 and 1947. What the British called the Sepoy Mutiny and Indians called the First War of Independence was a bloody and violent beginning. But that's what it was -- the beginning of a process that was unstoppable. It triggered a national consciousness and rebellion, culminating in Gandhiji's freedom movement.

Gandhi is known to have acknowledged that Mangal Pandey was the seed that sprouted as the freedom struggle. What Pandey did served as the counterpoint to the non-violent movement of Gandhi. I was happy to hear Leo Pescarolo, an Italian journalist, who was on one of the Locarno juries this year, commenting on the film: 'In a dying world,' he said, 'you see the strength of a nation.'