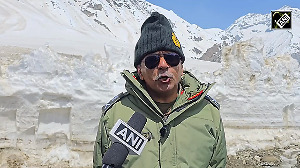

Devi Singh Bhati, president of the Rajasthan Samajik Nyay Manch or the Rajasthan Social Justice Front, is on a mission. To right the wrongs that have crept into the policy of reservations.

A minister in Bhairon Singh Shekhwat's Bharatiya Janata Party government and one of the few BJP legislators to withstand the Congress wave of 1998, he was expelled from the party in September for his views that did not go down well with the central leadership.

Both Bhati and Manch Vice-President Suresh Mishra dispel the belief that the Manch is seeking reservations for the economically weak upper castes or else, a ban on reservations, which is guaranteed in the Constitution. Both men say they are not against reservations per se, but are against the use of reservations for political purposes and the extension of reservations to groups that do not deserve them.

"Poor tribals and Dalits, who have suffered injustice for centuries, of course, need help. In fact, we want to help the poorest of the poor get social justice," points out Bhati, "And while caste is permanent, economic status can vary from year to year, even from day to day. That makes it impossible to have reservations based on economic criteria. What happens if a poor person who seeks reservations tomorrow becomes rich; will he be then expelled from the reserved seat he holds? It is for this reason that Nehru was against economic status for reservations."

Bhati and the Manch are against castes that do not deserve the benefit of reservations and are yet given the facility, often to the detriment of those who deserve it. Case in point is the inclusion of the Jats as part of the Other Backward Classes, a term applied to various so-called low caste people. The Manch believes the Jats have garnered facilities meant to help socially and economically backward castes.

"Including Jats was nothing more than vote-bank politics," insists Bhati, "They keep claiming to support one political party against the other and, in their nervousness, they then claim to deserve reservations." The Jats, who are spread across northern and eastern Rajasthan, Haryana, western Uttar Pradesh and Punjab (where the Jats are mostly Sikhs), were originally a cultivator class that rose in status after they took up arms to attack the declining Mughal empire in the 18th century. Jat kingdoms, while not half as numerous as Rajput kingdoms, dot the landscape in the region around Delhi.

The Jats, who are spread across northern and eastern Rajasthan, Haryana, western Uttar Pradesh and Punjab (where the Jats are mostly Sikhs), were originally a cultivator class that rose in status after they took up arms to attack the declining Mughal empire in the 18th century. Jat kingdoms, while not half as numerous as Rajput kingdoms, dot the landscape in the region around Delhi.

Chaudhary Charan Singh, prime minister for six months in 1979, was a Jat; and the Green Revolution across Haryana and western Rajasthan have seen the community prosper. Jats are also present in large numbers in the armed forces; the Jat Regiment is one of India's oldest regiment, raised by the British who saw them as a martial race.

The former rulers of Dholpur -- Vasundhara Raje, the BJP's leader in Rajasthan, is the former maharani of Dholpur -- and Bharatpur in Rajasthan are Jats. "Why do members of royal families need reservations?" he asks. "Reservations were created to help the poor and the depressed. Are these people in any sense poor or depressed?"

He hastens to add that even the Nawab of Tonk, a Muslim, has been listed as an OBC by the Rajasthan government.

The Samajik Nyay Manch claims membership of various so-called upper caste groups such as the Rajputs, Vaishyas (Banias), Kayasths, Brahmins, Punjabis and Sindhis. By including Jats as OBCs, Manch leaders say other OBC groups have suffered.

"There are 269 OBC castes across Rajasthan, yet the benefits go to the Jats simply because of these reservations," says Manch Vice-President Mishra. "In the most recent recruitment drive for the Rajasthan Administrative Service a couple of years ago, 85 seats were reserved for OBCs and 79 of these were bagged by the Jats. Six pradhan (district heads) seats were reserved for OBCs; all were taken by Jats. Of the 105 sub-inspector (of police) posts reserved for OBCs, Jats got 104 of them. What will happen to the other OBCs for whom reservations were actually created?"

The Centre included Jats as OBCs in 1999 after much lobbying by various Jat groups. But while the central government restricted the reservations for Jats to government jobs, Ashok Gehlot's government in Rajasthan extended the reservation to education institutions. The Manch sees the extension as a political sop to make amends for the fact that the Congress, after hinting it would appoint a Jat as chief minister, put Gehlot -- a non-Jat OBC -- in the chair.

Jats comprise about 10 per cent of Rajasthan's 44 million people and hold 33 of the state's 200 assembly seats.

Is the Manch demanding that Jats be excluded from the OBC list?

"No, we are demanding that the Rajasthan government do what other states have done: within the OBC category, create three sections of backward, more backward, and most backward. This will ensure that the most and more backward castes, who are unable to compete with the Jats, also get fair representation in education institutions and in government jobs," says Bhati.

It is politics, he says, that prevents the Congress government in Rajasthan from implementing this policy, which was created after a Supreme Court order. It was his speaking up for this policy, he adds, that made the BJP expel him.

"Both the political parties are scared of the Jats because in the 1998 assembly election, the Jats claimed they had dumped the BJP for the Congress and the latter won, while in the Lok Sabha election in 1999, they said they had supported the BJP since the Congress did not appoint a Jat chief minister, and the BJP won more seats in Rajasthan," he says.

But the case against the Jats is not the Manch's only grouse. In 1999, the Gehlot government's order on OBC reservations had another ruling, by which all people employed in professions that were inherited would be categorised as OBCs. This rule was enacted to help poor artisans and landless cultivators, who, trapped in a cycle of poverty and lacking education and employment opportunities, end up taking the jobs their fathers pass down.

In 1999, the Gehlot government's order on OBC reservations had another ruling, by which all people employed in professions that were inherited would be categorised as OBCs. This rule was enacted to help poor artisans and landless cultivators, who, trapped in a cycle of poverty and lacking education and employment opportunities, end up taking the jobs their fathers pass down.

But this rule on inheriting traditional occupations also included the high priests of Rajasthan's three biggest temples: the Nathdwara temple near Udaipur; the Balaji temple (modelled after the famous Venkateswara temple in Tirupati) at Mehndipur, Dausa; and the Govind Devji temple at Jaipur.

This meant the Brahmins of these three temples are OBCs, on a par with herdsmen, farmers, weavers, etc.

"Nathdwara temple receives Rs 60 crore (Rs 600 million) annually as donations. The priests of these temples own bungalows in Mumbai, and yet they get reservations? But thousands of poor priests who look after numerous temples in the state are excluded. What kind of social justice is this?" asks Bhati angrily.

The Manch is not asking that the Brahmin priests be derecognised as OBCs but that the priests of all temples in Rajasthan be recognised as OBCs and allowed the facility of reservations.

Bhati points out that after the Supreme Court ruling in 2002, a temple priest's profession is no longer restricted to a Brahmin or any particular caste but open to all Hindus, regardless of caste. "Anyone can be a temple priest now. What we are saying is why are the richest temples' priests getting benefits while the poor ones are not?" he says.

"We believe reservations should exist, but it must be there to help those who need it, not those with political or economic clout," adds Bhati. "Our mission is to right that wrong, and we have received huge support for our cause."

Founded in 1999, the Manch was registered as a political party this year and is contesting 63 seats in Rajasthan. It has tied up with smaller parties and Independent candidates who support the Manch's point of view and hopes to influence the outcome in at least 130 seats.

After the assembly election, Bhati says he will look to spreading his message to other states since many of his concerns -- especially the fact that reservations over the years have benefited only a small section and largely ignored those who need it most -- are applicable across India. He could find many supporters.

© 2025

© 2025