In the cloistered hush of the Lord's museum a tiny, unremarkable pottery urn has attained an importance out of all proportion to its size.

Standing only 10 cms high, the urn contains the burnt remnants of a bail. It commemorates a famous mock obituary in the Sporting Times, announcing the death of English cricket after a seven-run loss to Australia at The Oval on August 29, 1882. "The body will be cremated and the ashes taken to Australia," the notice concluded.

Standing only 10 cms high, the urn contains the burnt remnants of a bail. It commemorates a famous mock obituary in the Sporting Times, announcing the death of English cricket after a seven-run loss to Australia at The Oval on August 29, 1882. "The body will be cremated and the ashes taken to Australia," the notice concluded.

Australia fast bowler Fred Spofforth inspired the Sporting Times' lament, transforming the one-off match through fierce, controlled pace. A theme had been established for one of the world's great sporting rivalries, to be forever known as the battle for the Ashes.

Test cricket between England and Australia had already been in place for five years as Victorian Britain fulfilled its self-appointed destiny and took cricket along with other aspects of British culture to the colonies.

Already an important division had emerged. English cricket reflected the class divide, with county and international teams dividing into gentlemen (amateurs) and players (professionals). Australians were simply men who played cricket for recreation, establishing early the sometimes aggressive egalitarianism which was to characterise their nation.

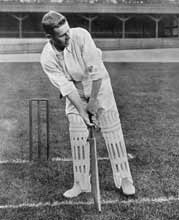

The late 19th and early 20th centuries were a golden era for batsmen.

On the England side there was C.B. Fry, scorer of six consecutive first-class centuries, world long-jump record holder and a man who was later to reject an offer of the throne of Albania. Fry was partnered at Sussex by the Indian wizard K.S. Ranjitsinjhi.

GRACE ENDORSEMENT

The pair colluded in "The Jubilee Book of Cricket" to pay tribute to the greatest Victorian, W.G. Grace who captained England in five Ashes series. "He turned the old one-string instrument into a many-chorded lyre," was their ringing endorsement.

On the Australian side, Victor Trumper, who was to die tragically young, was regarded by his contemporaries as the beau ideal of style and daring.

On the Australian side, Victor Trumper, who was to die tragically young, was regarded by his contemporaries as the beau ideal of style and daring.

After the horrors of World War One had shattered the long, languid Edwardian summer, Warwick Armstrong, known as the Big Ship because of his immense bulk, took a side to England in 1921 featuring two express bowlers.

Ted McDonald was swift and chillingly forensic, employing precise variations at pace. Jack Gregory, with a giant kangaroo leap, bowled wide of the return crease with undisguised aggression. Australia won 3-0.

The pendulum swung towards England in the late 1920s. On the 1928-9 tour of Australia, Wally Hammond, a majestic driver through the covers, stamped his country's authority with a tally of 905 runs at an average of 113.

In the opposition a slight, pale-faced newcomer took note.

On the 1930 tour of England the 21-year-old Don Bradman, responded with 974 runs at an average of 139 including a world-record 334 at Headingley in Leeds to ensure the Ashes returned south of the equator.

Bradman thought his 254 in the Lord's Test was the better innings with each precisely calibrated stroke going exactly where he intended. Neville Cardus of the Manchester Guardian agreed. His choice of imagery was instructive.

"Never before this hour, or two hours until close of play and never since has a batsman equalled Bradman's cool deliberate murder. Bradman...played the most brilliant and dramatically incisive and murderous innings of his career...an innings which was beautiful and yet somehow cruel in its excessive mastery."

THE GREATEST

Unlike almost any other major sport, there is no disputing the identity of the greatest cricketer of all time. Bradman averaged roughly 40 runs more per innings than his nearest rivals and attained celebrity status afforded to none of his contemporaries. Political and economic forces in his sunburnt continent were to force an essentially private man into a role he neither wanted, expected or embraced.

In common with the remainder of the western world, Australia was gripped by the Great Depression in the early 1930s.

Resentments in a population swelled by Irish immigrants with no great love of Britain were heightened by what seemed the heartless indifference of the London banks to their plight.

Into this fraught atmosphere an England side led by Douglas Jardine arrived for the 1932-3 Australian season. Jardine, born in India and educated at Winchester, was the type of Englishman Australians love to hate. Their dislike was fully reciprocated by Jardine who instructed his Nottinghamshire professionals Harold Larwood and Bill Voce to bowl short and fast and directly at the bodies of the Australian batsmen to a packed legside field.

The particular target was Bradman. The nimble-footed Australian responded with quick-witted improvisation but his series average was cut to a mortal 56. England went home with the Ashes, but not before riots at packed grounds were narrowly averted and diplomatic relations between the two countries briefly threatened after Australia accused England of unsportsmanlike behaviour.

Normal service was resumed for the remainder of the 1930s as bowlers laboured on lifeless pitches. An interminable 364 by Yorkshireman Len Hutton in one of the unlamented timeless Tests when games were played to a conclusion, ensured a drawn series for England in 1938. It was to be the last match between the two countries before war again erupted in Europe.

Cardus once recalled how World War Two was recognised at Lord's on the day Germany invaded Poland.

Standing in the Long Room, Cardus and a Lord's member watched two workmen carry away a bust of Grace. "Did you see sir?", asked Cardus's companion. "That means war."

POST WORLD WAR TWO

After World War Two, an emotionally and physically exhausted Britain welcomed the 1948 Australian cricketers with an unprecedented warmth laced by heartfelt relief that the Empire had been saved.

Don Bradman's men were feted by society in a war-ravaged country and their matches were sellouts. Fortuitously the Australia side was probably the finest ever assembled.

In his 40th year, Bradman had to conserve his energies but his appetite for runs was as voracious as ever.

No keener brain ever applied its powers to a ball game than Bradman's and his side, spearheaded by the pace duo of Ray Lindwall and the incomparable all rounder Keith Miller, achieved his ambition of completing a lengthy tour unbeaten.

Famously Bradman, needing just four runs to achieve a lifetime Test average of 100, was bowled second ball at The Oval for a duck.

Famously Bradman, needing just four runs to achieve a lifetime Test average of 100, was bowled second ball at The Oval for a duck.

Len Hutton, England's first professional captain who as an opener bore the brunt of the Lindwall-Miller assault with stoic skill, was to take a particularly satisfying revenge.

Alec Bedser, the great-hearted medium-fast inswing bowler with a deadly leg cutter that had bothered Bradman, bowled England to victory in the 1953 Coronation Tests.

Frank Tyson, a balding schoolteacher who poured all his energies into one prodigious season of blinding pace bowling, won the 1954-55 series in Australia. In 1956 it was the turn of the laconic off-spinner Jim Laker, who made the ball hum like a hornet through the air as he took 19 wickets in a single Test at Manchester.

THROWING CONTROVERSY

By now England were captained by Peter May, possibly the best of England's post-war batsmen with his crisp upright driving. He was also a ruthlessly tough captain in an era of dour, attritional Test cricket.

May led a side to Australia in 1958 acclaimed at home as the best to leave English shores. They ended up comprehensively beaten 4-0 by a revitalised opposition captained by Richie Benaud who had emerged from a long apprenticeship to become the best leg spinner in the world.

More dubiously Australia also fielded a number of bowlers, notably Ian Meckiff, whose actions were at best highly suspicious.

Bradman, who was to become almost as influential an administrator as he was a player, was unanimously elected as chairman of the Australian Board of Control in 1960. After prolonged negotiations with the other members of the old Imperial Cricket Conference the throwing problem, which was not confined to Australia, was stamped out and Meckiff was not selected for the 1961 tour of England.

The 1960s began in deceptively bright fashion as Australia (encouraged by Bradman who feared justifiably that Test cricket had become dangerously moribund) matched the extroverted West Indies side in a magnificent series. Unfortunately the excitement did not transfer to the Ashes arena where Australia managed to cling on to the urn for a decade although England usually looked the stronger side.

MODERN ERA

The modern era began in 1970-1, when Ray Illingworth, like Hutton a Yorkshire professional to his core, took an experienced, streetwise side to Australia.

The two pivotal players were John Snow, a moody fast man who cut the ball sharply off the pitch with disconcerting bounce, and the even more enigmatic Yorkshire opener Geoff Boycott. Between them they brought the Ashes back to England.

Four years later a series in Australia proved a sustained nightmare for the England batsmen. Dennis Lillee, who had made an impressive debut in the 1970-1 series, returned after a serious back operation to confirm he was a fast bowler to rank with Larwood and Lindwall. Jeff Thomson may have looked as if he had just stepped of a beach but his Catherine wheel delivery after a brief jog to the wicket was an athletic marvel and he propelled the ball faster than anybody since Tyson.

The return of Boycott after a self-imposed exile and the emergence of Bob Willis, a gangling fast bowler with a passion for the music of Bob Dylan and Wagnerian opera, helped to overcome an Australia side divided by the impending Kerry Packer rebel series.

Four years later Willis, on the verge of disappearing from the Test arena, took eight for 43 in the most astonishing Ashes victory of all. Ian Botham had resigned from the England captaincy before he was sacked. Revitalised under the guidance of the recalled guru Mike Brearley he struck 145 not out at Headingley after England had been asked to follow on.

Set 130 to win, Australia were swept aside by Willis. Botham returned match-winning performances in the next two Tests with first ball then bat, to complete the astounding turnaround.

England, with Botham usually prominent, won three series in the 1980s against Australia, this time weakened by defections in rebel tours to apartheid South Africa, while contriving to lose to almost everybody else.

Their idyll entered abruptly in 1989 when Australian captain Allan Border, heartily sick of fighting in a losing cause for most of the decade, began, with coach Bobby Simpson, to revive his country's fortunes.

The result has been one of the most successful, sustained reigns in sporting history. Australia, with runs galore from Steve Waugh, demolished a disjointed England side. They have not lost an Ashes series since and, by beating a fading West Indies side in 1995, they have been world number one for the past 10 years.

The result has been one of the most successful, sustained reigns in sporting history. Australia, with runs galore from Steve Waugh, demolished a disjointed England side. They have not lost an Ashes series since and, by beating a fading West Indies side in 1995, they have been world number one for the past 10 years.

In the process the Australians have produced three players who would be automatic selections for any mythical all-time Australian XI.

Shane Warne has revived the forgotten art of leg spin bowling and the destructive Adam Gilchrist has proved the most successful wicketkeeper-batsmen produced by any country. They will both be on display in the first Test of the latest series at Lord's next week along with Glenn McGrath, the meanest and tightest Australian new ball bowler in history and the latest in a line stretching back to Fred Spofforth who won the initial Ashes test of 1882.